By Frank Brockners

The Linux Foundation invited me to participate in a roundtable discussion on Agentic AI at this year’s Open Source Summit Europe 2025 in Amsterdam. Agentic AI is evolving rapidly and promises increased productivity, reduced operational cost, improved customer experience, and additional sources of revenue.

In preparation for the discussion and afterward, I collected a few thoughts around three key themes that I would like to share here:

- Technology and audience: Agentic AI is evolving—and the different phases solve different problems for different audiences, with different key technical requirements involved.

- The role of open source: As with any new technology, many approaches have emerged to cover the key technical requirements, which leads to a need to consolidate and, more importantly, integrate technologies into stable and easily consumable solutions. Open source is seen as the vehicle to drive this required integration and harmonization toward stable industry standards.

- The role of the developer: Large language models and Agentic AI can write code—which raises the obvious question of how this will impact the current role of developers.

TL;DR

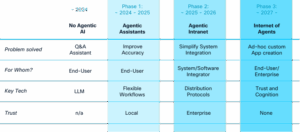

Agentic AI marks a paradigm shift in artificial intelligence, moving beyond single-shot LLM outputs to systems that pursue goals, make decisions, and act autonomously. Its evolution can be understood in three phases. The pre-agentic era resembled Daniel Kahneman’s “System 1” thinking—fast but superficial—limited to brittle chatbots, rigid expert systems, and fragile integrations. Phase 1 (roughly 2024–2025) introduced agentic assistants, where structured reasoning, planning, tool use, memory, and collaboration transformed LLMs into workflow engines capable of producing actionable results. Phase 2 (roughly 2025–2026) extends these systems into distributed “Agentic Intranets,” where agents collaborate across APIs and enterprise systems using natural language, reducing the cost and rigidity of traditional integration while introducing new challenges of trust, identity, orchestration, and semantic connectivity. Phase 3 (probably 2027 and beyond) envisions a global “Internet of Agents” in which trustworthy, auditable agents dynamically compose themselves into applications in response to human intent, enabling adaptive, large-scale collaboration across industries and domains. In Phase 1, the Internet shifted from “searching for information” to “receiving answers to questions.” Phases 2 and 3 move further, toward an Internet where we can ask the “Internet of Agents” to perform tasks on our behalf by dynamically generating ad hoc applications. Historically, we searched the Internet. Today, we ask questions. Tomorrow, we may see applications composed in our browsers that act directly on the intent we express.

The success of this evolution depends on open, collaborative ecosystems such as AGNTCY.org, is to serve as a collaboration hub for open-source initiatives, and fold in the work of standards bodies to create the test, integrate and evolve the required protocols and frameworks for interoperability, trust, and governance. For developers, Agentic AI shifts the role from writing code line by line to orchestrating, validating, and guiding intelligent coding agents, requiring new skills in precise requirement definition, workflow design, and systems thinking. As enterprises move from demonstrations to production-scale systems in 2025, the groundwork is being laid for an “Agentic Network Society”—one where software is built, integrated, and scaled through autonomous collaboration at both enterprise and global levels.

Introduction

Agentic AI refers to artificial intelligence systems designed not just to generate outputs, but to pursue goals, make decisions, and act autonomously. But there is more to it. The term “Agentic AI” is often used as if it describes a single transformation and set of technologies. The reality is more diverse. The evolution of Agentic AI can be broken into three distinct phases—each motivated by a different problem statement, using a different set of technology building blocks to solve the problem, and addressing a different audience or “persona,” as marketers like to call it.

Three forces are driving the emergence of Agentic AI. First, while today’s LLMs are linguistically fluent and provide access to vast amounts of semantically meaningful knowledge, they often lack the ability to perform complex tasks, ensure reliability, retain long-term memory, and interact effectively with third-party systems. Second, enterprises still struggle with costly and brittle integration across siloed systems, APIs, and datasets.

Microservice architectures have solved some challenges of distributed systems, but the API integration problem remains. Custom solution development and the associated system integration are OPEX‑intensive efforts. These limitations create demand for systems that can plan, adapt, and interoperate more flexibly—enabling us to replace classical services (custom solution development and system integration) with software. Third, application composition is still a manual task. Humans must translate the intent for a new application—what it needs to look like and do—into a set of components and their composition. Humans compose applications based on semantic understanding of the components and the required outcome.

Agentic AI offers a path forward. It moves us from single‑shot Q&A interactions to self‑organized workflows, and eventually to intent‑driven application composition on a global scale. Distributed agentic applications require a suite of new components and protocols. And if we want new applications to be automatically created for us based on an intent we express, AI will need to compose applications automatically—out of trustworthy components that have been assessed and tested beforehand—much like you take job candidates through a set of interviews and assessment centers.

Open‑source collaboration is the primary means to ensure seamless integration and interoperability—across the efforts of standards bodies and open‑source projects that deliver individual components.

As Agentic AI evolves, it will start to complement and change the lives of developers. Coding is starting to change—and with “vibe coding,” we’re beginning to use AI as we use compilers today. Developers will focus more on crisply articulating requirements and architecture than on writing code themselves, and their role will evolve with the different phases of AI. Hardly anyone writes assembler code today – nor do we review and challenge the assembler or byte code that our compilers create. While initially developers might still design the agentic workflows and wire agents to each other, in future phases more and more will be delegated to agentic systems that support the developer – moving the developer to take on the role of a first line manager of coding minions.

Phase 0 – Before Agentic AI

Before the rise of agentic approaches, large language models were used primarily as question‑answering machines, quite often with mediocre outcomes. Chatbots provided single‑shot answers to prompts, and quite frequently the answers lacked the desired accuracy. On the flip side, expert systems encoded knowledge into rigid ontologies that could provide accurate results but were limited in their domain coverage and were hard to maintain. Customized enterprise software relied on brittle API contracts, and integration against these APIs required a lot of custom development and a detailed understanding of the API. These systems could respond to questions, but they could not reason, adapt, or act independently.

Psychologist and Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman distinguished two modes of thinking that guide human decision‑making: System 1 and System 2. System 1 is fast, automatic, and intuitive—it relies on mental shortcuts and gut reactions to quickly process information. In contrast, System 2 is slow, deliberate, and analytic. It engages when tasks require focus, logic, or problem‑solving. While System 1 helps us navigate daily life efficiently, it can lead to biases and errors, whereas System 2, though more accurate, demands effort and mental energy. The pre‑agentic era resembles “System 1” thinking: fast, automatic, and heuristic‑driven. Like System 1, non‑agentic AI was effective in narrow situations but easily misled, unable to doubt its own conclusions, and incapable of building deeper understanding.

As expectations for AI grew, these limitations became clear. Businesses required systems that are comprehensive, respond with accuracy, carry out specific tasks, and can handle ambiguity, learn from experience, and perform tasks without constant human oversight.

Phase 1 (approx. 2024–2025): Agentic Assistants

Kahneman’s System 2 is about deliberate, rational, and analytical thinking. Just as System 2 checks and corrects the impulsiveness of our System 1, Phase 1 early agentic systems bring structured reasoning to LLMs, making them more dependable and actionable—and delivering better results.

The first step toward Agentic AI can be considered an approach to improve the results provided by large language models. At this stage, the primary problems addressed were the inaccuracy of LLM‑generated answers and their inability to perform real‑world actions. Researchers found that LLMs performed better when given very specific, concise tasks—and, much like humans, achieved better results when the model was told to create a plan for how to tackle the question, break the task into smaller steps, and reflect on the results before responding.

In the initial phase, Agentic AI addressed these shortcomings by enabling LLMs not only to produce answers but also to plan, decompose tasks, and execute workflows. Instead of responding with a static piece of text, an agent can break down a request into subtasks, reason through the steps, and call external tools or APIs.

In this first phase, it is still the human who defines how an LLM will tackle a problem. As a result, human‑defined workflows became the main means to enable the first phase of Agentic AI. Similar to a junior engineer whose manager provides detailed, step‑by‑step guidance on how to approach a problem, one needs to define the workflow for how the LLM is to approach the problem.

Consider the example of a travel assistant. A conventional chatbot might suggest a list of flights in response to a query. An agentic assistant, however, can go further: it searches across providers, compares options, reserves the ticket, and integrates the booking into the user’s calendar and expense system.

To support such behavior, agentic assistants rely on several capabilities. They must plan ahead, keeping track of intermediate steps; they must access external resources through tool calling; they must remember previous interactions and decisions; and they must be able to reflect, revising their strategies if the first attempt fails. Frameworks such as LangGraph, CrewAI, AutoGen, Pydantic, n8n, Semantic Kernel, etc. emerged to orchestrate these workflows. These frameworks support the key design patterns of agentic AI systems of phase 1: (1) Planning—make the system think through the steps required to solve a problem upfront; (2) Tool calling—make the system understand which tools are available to solve the problem and how to use them; (3) Reflection—enable the system to iteratively improve results through critique, suggestion, and reasoning; (4) Collaboration—enable multiple agents with different roles to communicate and collaborate; and (5) Memory—enable the system to track progress and results and learn, both per agent and across the whole system.

Phase 1 laid the foundation for an even larger leap. Agentic assistants, while broad in application, are still primarily focused on improving human-to-machine interaction. In doing so, however, Phase 1 also opened the door to advancing machine-to-machine interaction—which accounts for the vast majority of communication today. History offers several examples where a targeted solution evolved into the basis for a much larger transformation. Consider shipping containers, invented in the 1950s to make cargo handling at ports faster and more secure. Over time, they became the foundation for standardized intermodal transport, enabling global supply chains, just-in-time manufacturing, and globalization itself. Or take the Universal Product Code (UPC), introduced in the 1970s to speed up supermarket checkout and reduce pricing errors. It later enabled real-time inventory management, automated restocking, global retail integration, and supply chain optimization. Similarly, the Global Positioning System (GPS), originally developed for precise military navigation, went on to revolutionize civilian infrastructure—supporting global time synchronization for power grids and financial systems, enabling fine-grained traffic control, improving aviation safety, and advancing precision agriculture.

The next phase represents a similar transition—from a targeted solution to a far more foundational shift, with agentic systems redefining software and systems integration. One notable side effect of agentic assistants, originally designed to deliver accurate responses, is that they provide software with a natural language interface. This means software can now communicate with other software in natural language, eliminating the need for rigid API contracts.

Phase 2 (approx. 2025–2026): Agentic Intranets

While structured thinking and an inner monologue—System 2–type thinking—enable humans to achieve great results, it is the ability to collaborate with other humans that sets us apart from any other species. One of Yuval Harari’s key hypotheses in his book Sapiens is that Homo sapiens succeeded not because of superior strength or intelligence alone, but because of the ability to cooperate flexibly in large groups. In the same way, the Agentic Intranet enables digital cooperation at scale, allowing enterprises to build adaptive applications faster and at lower cost. Phase 2 unveils the transformative power of agentic AI from a business perspective – as it changes how software/machines talk to software/machines, which is by far the predominant interaction today.

Once agentic assistants proved effective, the industry quickly realized that not all resources and tools reside in a single place and that access to APIs, tools, and resources is diverse. An early recognition of that fact was the arrival of the Model Context Protocol (MCP) in November 2024, which standardized how models interact with tools and other resources—and, equally important, enabled an LLM to reach tools and resources at different locations. What was originally planned as a means to help the LLM provide better answers turned into a means to simplify integration with remote APIs, because LLMs could leverage those APIs without detailed knowledge of the API definition (e.g., an OpenAPI spec) but by using simple natural language. Initiatives like A2A, released in April 2025, further expanded these capabilities by enabling agent-to-agent connections. Software is now able to “team up” like humans. Humans can collaborate, despite not knowing each other well – the same is true for software now.

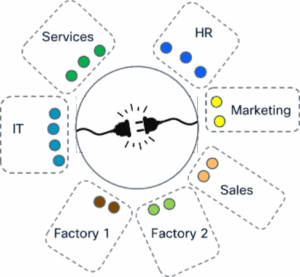

Custom enterprise applications have traditionally been slow and expensive to develop because they require the integration of multiple components and the associated data across departments or even companies. The industry has made several efforts to simplify the creation of distributed applications, from the early days of web services to more recent microservices architectures. While successful, the requirement to have a detailed understanding of each component’s API to accurately and securely “wire” the components persisted. APIs, while useful, are rigid, brittle, and costly to maintain.

Agentic Intranets address this challenge by transforming enterprise components and the associated data into trusted agents. Rather than forcing developers to code every integration manually, these agents can communicate through natural‑language protocols, negotiate workflows, and compose themselves into larger applications. In practice, this means that HR, finance, logistics, and IT systems can collaborate dynamically without predefining every possible interaction. What was originally a human‑to‑machine, chatbot‑style communication pattern rapidly transforms into a machine‑to‑machine communication pattern—but rather than using classic and brittle protocol‑level integration, machine‑to‑machine communication now uses natural language. Humans can communicate with other humans they hardly know in natural language—similarly, machines can now talk to other machines without knowing the exact interface specification of the peer. Natural language is sufficient.

When creating distributed agentic systems, some of the classic challenges for distributed systems have to be addressed: connectivity, identification, discovery, orchestration, authentication, monitoring, and security. At the same time, the use of a semantically loose coupling between components using natural language—rather than well‑defined schemas—poses new challenges. In addition, LLMs are by their very nature probabilistic systems. Agents do not behave deterministically, surfacing additional challenges for system testing, reliability, and predictability.

Despite the challenges, the benefits for enterprises are significant. Agentic AI started as an approach to make LLM responses better. The first phase targeted the end user. The second phase of Agentic AI turns it into a system‑integration play. The main audience for Phase 2 are those who do custom software solutions for a living: service and system integrators—or the IT departments of enterprises.

From a technology perspective, flexible workflows—ranging from simple to complex—were the foundation of Phase 1. A wide variety of frameworks to create, operate and maintain these agentic workflows emerged, and new ones continue to appear, enabling users to create agentic workflows quickly and efficiently.

The technology focus for Phase 2 is solving the distribution problem—i.e., it is a protocol and federation play rather than a workflow‑engine play as in Phase 1. It is about enabling distributed ensembles of agents—which means identification and discovery of agents, connectivity among agents, and securing and observing distributed ensembles of agents are the key technology pillars. Multi‑agent ensembles can coordinate distributed tasks; directories and identity services make agents discoverable across the organization; secure connectivity and federated discovery ensure that agents can find each other safely; task‑based access control enforces policy; and monitoring tools provide visibility with minimal or even no instrumentation: one can add an “observer agent” to an agent‑to‑agent communication so that the observer can monitor and analyze the communication of the agents without any impact on the communicating agents. Phase 2 is about building the “glue” between agents that reside in different organizations or locations—specifically, the mechanisms and protocols that enable connectivity and federation while accommodating diverse implementations. Consider an example: Each organization may implement its own agent directory and the implementation might differ between organizations, but the protocol suite of Phase 2 ensures that these local directories can be interconnected into an enterprise-wide system. This allows agents outside the local directory to be discovered and accessed when a discovery request originates from within the organization.

Phase 3 (expected 2027+): The Internet of Agents

The logical extension of the Agentic Intranet is the “Internet of Agents”—a global ecosystem where trusted agents can discover one another, connect, and compose themselves into applications on demand. Historically, we searched the Internet for references. The first phase of Agentic AI transformed this process into question-answering, as reflected in the rise of “zero-click” searches. A worldwide ecosystem of agents could advance this further, shifting from systems that merely provide answers—leaving the user to act on them—to systems that take action directly based on articulated intent. Imagine describing a need or goal, and your browser automatically assembles an agentic application on the fly, tests and validates it in a sandbox, and then executes your intent. You could choose to save this “ad hoc application” for future use—turning it into an app on your phone or computer—or simply discard it if the task was a one-time need.

Sociologist Manuel Castells described modern society as a network society, where power and structure reside not in institutions but in the networks themselves. The Internet of Agents embodies this vision: a distributed, trusted, global system in which agency is no longer centralized but flows through autonomous, interconnected agents.

The central challenges in this phase are trust and intent‑driven composition. Instead of manually designing integrations, users or enterprises can simply state an intent—such as “set up a supply chain for sustainable materials” or “create an app for my phone that integrates all my bank accounts”—and the system automatically assembles the required agents into a functioning application. This process may create short‑lived, ad hoc systems or long‑lived, persistent multi‑agent networks. The key asset of such a system is trust: agents found on the global Internet need to be assessable and auditable – and the same is true for multi agent systems. Much like when we interview and assess a human candidate for a job, we need to understand who the agent is, what its expertise and qualifications are, what its track record is, how trustworthy it is, and whether there are known issues or past “misbehaviors.” Similarly, when agents are combined into multi-agent systems, they must be assessed like human teams—recognizing that a collection of strong individuals does not automatically form a strong team.

As such, every SaaS platform, public API, or service will be represented by an agent with verifiable identity and auditability. These agents will be discoverable across the Internet, will be continuously assessed for trustworthiness, and will be replaceable if they underperform – or they might even be banned. Trust frameworks—including sandboxed and canary deployments—allow new agents to be tested before they are widely adopted. Semantic discovery ensures that agents are described by what they can do, not just their technical endpoints, while automated assessment tools evaluate multi‑agent systems and suggest improvements.

We Can Only Do This Together

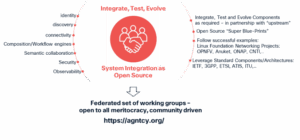

The vision of a global agentic ecosystem, a network society of agents, cannot be realized by any single organization. Ecosystems grow and are composed of multiple entities in an open, democratic, and merit‑focused process with open governance. Identity, interoperability, and trust require collective action and shared standards. Open source—governed by a well‑recognized, open foundation—is a natural approach to facilitate such an effort.

AGNTCY.org is emerging as an open‑source collaboration hub. Its purpose is to ensure interoperability of different agentic building blocks—gateways, directories, protocols, etc.—to integrate, test, and also provide the infrastructure for agentic ecosystems—covering identity, catalogs, directories, communication, semantic collaboration, composition, observability, and security. The initiative operates under principles of open governance, following models established by the Linux Foundation. Multiple federated working groups collaborate on different aspects of the ecosystem, with the mission to integrate diverse projects and standards into “Super Blueprints” that can be tested and standardized—and to fill the gaps if missing pieces are identified.

By combining and integrating the work of open source projects like A2A or Agentgateway and working with established Standards Development Organizations such as IETF, 3GPP, ETSI, and ITU, open source initiatives like AGNTCY can ensure that community‑driven solutions evolve into widely accepted industry standards. For example, IETF started to tackle several authentication and security related topics for agents (see e.g., draft-rosenberg-oauth-aauth, draft-rosenberg-cheq, draft-nandakumar-agent-sd-jwt) – and in Aril 2025 chartered the new AI Preferences (AIPREF) Working Group that will work on standardizing building blocks that allow for the expression of preferences about how content is collected and processed for Artificial Intelligence (AI) model development, deployment, and use. This approach reflects the philosophy of “rough consensus and running code”: practical, collaborative innovation that accelerates adoption across industries.

Mark Collier, General Manager of AI & Infrastructure, Linux Foundation, summarized it nicely at a roundtable discussion at the Open-Source Summit Europe 2025: “There is no other way than to do this together.”

What Does Agentic AI Mean for the Developer?

In his keynote at OSS Europe 2025, Jim Zemlin, Executive Director of the Linux Foundation, asked a set of questions about how AI will change the role of open source and software development in the next five years, including whether there will be fewer or more developers five years from now. While no one can answer that question right now, it is clear that there will be changes and shifts.

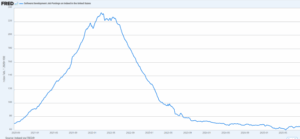

The rise of agentic AI is reshaping the role of software developers from code producers to orchestral leaders of intelligent coding agents. Instead of writing every line of code, developers are increasingly functioning as editors‑in‑chief—assembling, reviewing, and directing AI‑generated snippets much like managing junior colleagues. This transition demands a new skill set: crafting highly specific and unambiguous requirements for code rather than the code itself, structuring the task at hand into clear and specific steps (almost like a micromanager would do), and supervising agents to ensure correctness, security, and alignment with business goals. In practice, this elevates developers into first‑line managers of “coding minions,” responsible for guiding, validating, and correcting AI outputs. While senior developers may find this transition natural, early‑career engineers face challenges: without years of coding intuition to lean on, they must expand their education into business and systems‑level thinking to remain effective supervisors of AI. In his keynote, Jim cited several sources that indicate shifts in the job market. For example, he showed FRED data about software development job postings—which peaked in mid‑2022 and have declined sharply since—with junior engineers now struggling to secure roles, a trend highlighted in reporting such as the New York Times piece, “Goodbye, $165,000 Tech Jobs. Student Coders Seek Work at Chipotle.”

This mirrors past leaps in abstraction: just as compilers free developers from writing assembly language, agentic AI systems like Claude Code or OpenAI Codex write code in a specific programming language, leaving humans to focus on design intent, crisp articulation of the requirements and validation. In this environment, rigorous test coverage, CI/CD pipelines, and trustworthy sandboxes for AI‑generated code (so that you can test‑drive and automatically audit agent code that you, for example, found on Git—or that your coding minions created) become indispensable to build trust at scale. Platform engineers and SREs—who already support hundreds of developers—will start to also employ AI augmentation to manage the new complexity. CAIPE (Community AI Platform Engineering) that is part of the larger Cloud Native Operational Excellence (CNOE) initiative is a great example. AI will not only help with creating code but, more importantly, with validating the code against the original objectives and requirements, as well as inherent security needs.

“More eyes on your code” has always been the principle of open source—to ensure that robust and secure code is created. Experience in integration and testing focused open‑source projects like OPNFV/Anuket, CNTI or the 5G super blueprint (SPB) initiative of Linux Foundation Networking has shown that system integration as an open community effort can play a major role in creating solutions and components that meet the needs of service providers and enterprises.

The Path Forward

2025 marks the moment when agentic applications begin shifting from experimental demonstrations to production systems. Enterprises will adopt intranet‑scale multi‑agent architectures, while open collaborations will lay the groundwork for interoperability across industries.

Before the end of this decade, these foundations may give rise to the Internet of Agents—a global network of autonomous systems capable of cognitive computing at an unprecedented scale. Such a system could redefine how businesses, governments, and individuals engage with technology, creating what might be called an Agentic Network Society. We are already shifting from “searching the Internet” to “asking the Internet a question” (through platforms like Google, OpenAI, Perplexity, etc.) and expecting an answer. The next stage will be to “ask the Internet to perform a task”—where the system dynamically assembles a distributed, multi-agent application on your behalf. That application might reside on your phone or desktop computer, and it might run within an advanced form of a browser. There are some early indications for this trend with agentic AI browser companies like Fellou or Sigmabrowser – and several of the larger players besides Google expand their portfolio to include browser capabilities (Perplexity bought Sidekick, OpenAI plans to release a browser, Atlassian acquires the browser company).

Meanwhile, developers will gear up and take on the role of product owners and first‑line managers—focusing on a crisp articulation of the requirements rather than writing the code themselves. AI is just the next iteration of a compiler. Or as Erik Schluntz, Anthropic, put it: “Ask not what Claude can do for you, but what you can do for Claude.”

Conclusion

Agentic AI represents a paradigm shift in computing – complementing deterministic computing to probabilistic computing and using natural language as the glue to build large distributed systems. It is not simply an incremental improvement in model performance, but a transformation in how software is built, integrated, and scaled.

In its first phase, agentic systems make AI more accurate and actionable through applications that consist of local workflows that employ LLMs in specific roles and leverage tools. In its second phase, agentic systems reduce enterprise integration costs and enable new applications by flexible intranet‑scale collaboration among different software components/APIs. Agentic AI and its ability to integrate software and data using natural language as the vehicle, has the potential to overcome what is commonly referred to as Conway’s law, i.e., that software structure follows the organizational structure of an enterprise. And in its third phase, agentic systems unlock global‑scale, intent‑driven cognitive computing through the Internet of Agents. The Internet of Agents will turn an expressed intent into an ad-hoc application – running on your phone, desktop computer – as a standalone app or in a secure, agentic sandbox in your browser.

The success of this evolution will depend on open, collaborative ecosystems such as AGNTCY.org. By working together, enterprises, service providers, and the open‑source community can ensure that Agentic AI evolves into a trustworthy, interoperable, and inclusive foundation for the future of computing. Join the movement!